|

Search | FAQ | US Titles | UK Titles | Memories | VaporWare | Digest | |||||||

| GuestBook | Classified | Chat | Products | Featured | Technical | Museum | ||||||||

| Downloads | Production | Fanfares | Music | Misc | Related | Contact | ||||||||

| Memories of VideoDisc - Who's Who in VideoDisc | ||||||||||||||

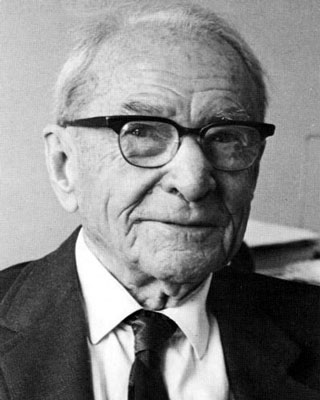

Vladimir Zworykin was one of the foremost television pioneers of the 20th century. In the 1920's he invented the kinescope which evolved into the picture tube used in billions of television receivers. Zworykin teamed up with David Sarnoff in 1929, a relationship that resulted in RCA's introduction of commercial television at the 1939 World's Fair. Although Vladimir Zworykin "retired" from RCA in 1954, he maintained an office at RCA Laboratories - reading his journals and showing interest in current research - right up until well after the CED system had hit the market.

In the past 24 years, Vladimir K. Zworykin has twice gone through the motions of retiring only to be drawn irresistibly back to work. Now at 89 he still drives to his office at Princeton's RCA Laboratories four days out of five, his distaste for enforced idleness as pronounced as ever. "I'll retire when I die," he says from behind a desk cluttered with journals from a dozen different professional societies, physics textbook manuscripts sent for his comments, and other fallout of a full schedule. "I don't ever expect to stop working."

Zworykin, of course, is known best as the Russian-born electronics pioneer who more than any other technical innovator made television possible. As an engineer with RCA in the 1920s he developed the first iconoscope and kinescope, which provided the basis for the camera and picture tubes, respectively, of modern TV. That achievement alone puts Zworykin on equal footing with Edison, Bell and the Wright Brothers. His 120-plus patents and 27 major awards and citations represent triumphs in gunnery controls, automobile technology, and most notably, medical electronics as well. And his collaboration in the 1940s with RCA engineer James Hillier produced the electron microscope, whose impact on biological research and the physical sciences has been inestimable.

On his first "retirement," at age 65 in 1954, Zworykin was elected honorary vice president of RCA and made a technical consultant to the company. ("Consultants are like geldings," he likes to joke. "They run with the other horses but don't participate.") In those twin capacities he keeps abreast of the Labs' multifarious research projects, breaking away for three months each winter with his wife Katharine to their beachfront home in Miami and his work as professor-scientist at the University of Miami.

"For me to attempt an idle retirement would be unthinkable," says the gentle-spoken Zworykin. "If it's in your nature to work all the time, you work all the time. Age means nothing." Until recently, he had been turning his efforts to developing an electronic acupuncture system that would replace needles with pain-killing electronic pulses applied at varying speeds to acupuncture points located with probes and a meter. "I built a unit in my home," he says, "and was able to relieve - if only temporarily - arthritic pains in my shoulders. One of the benefits of such a system is that someday, linked with computers, it might help us learn exactly why acupuncture works."

To be sure, the medical uses of electronics more than anything else seem to engage Zworykin's interest these days. "The workings of the human body fascinate him," says one Princeton colleague, "both as a physicist and a humanist. Once we were strolling on the grounds here when he started into an impromptu discourse on the physics of walking. His brain never shuts off." But Zworykin's involvement with matters medical is a logical outgrowth of a life spent extending the limits of man's senses.

"Back during my undergraduate days in Petrograd before World War I," he says, "I first became interested in the possibilities of television because it seemed a way of seeing things unviewable by the naked eye. In fact, I think the biggest achievement in television to date was the photographs broadcast from Mars. But there are parts of the human body historically as inaccessible as the Martian surface and the far side of the moon, and the human body is far too important to remain hidden."

When he retired from RCA in 1954, Zworykin became director of Rockefeller University's Medical Electronics Center in New York, where he developed the "endosonde," an FM radio transmitter-in-a-pill that, once swallowed, broadcasts data from the remoter regions of the patient's gastrointestinal tract.

Zworykin's passion for viewing the unviewable began over 70 years ago during his undergraduate years at the Imperial Institute of Technology in Petrograd. "From 1906 through 1912 I had the good fortune to study under Boris Rosing, the great Russian physicist," Zworykin says. "He took a liking to me and got me involved in a couple of projects of his - most notably his work on television, or, as he called it, 'the radio telescope.'" Rosing was trying to transmit pictures by wire in his own laboratory, he recalls, "but we both quickly came to see that an electronic system, using cathode ray tubes, would be far more practical than a mechanical one." By the time of Zworykin's graduation in 1912, student and teacher had built a primitive TV system whose performance suffered greatly because of its poor sensitivity to light. Zworykin, however, was hooked on television for life.

"From Petrograd I went to Paris and studied X-rays with Paul Langevin," Zworykin says. "After two years the Great War broke out and I found myself in the Russian Signal Corps, teaching soldiers how to operate radio equipment." The outbreak of the Russian Revolution and the ensuing chaos seemed to spell doom for Zworykin's future research and educational plans, so he vowed to emigrate to the U.S. "This was easier said than done," he says. "I couldn't get permission to leave Russia nor would the U.S. grant me a visa." After months of hiding from government authorities to avoid arrest, Zworykin found his way to the Allies' front lines at Archangel, where he buttonholed an American diplomat and spoke wildly about the possibilities of television.

"It must have seemed utterly fantastic to him," Zworykin says,"but he agreed to help me get my visa." Arriving in the U.S. in 1918, Zworykin found a $200-a-month assembly-line job with Westinghouse in Pittsburgh which he used as a springboard for attempting to sell his bosses on the idea of television.

"But they weren't listening," he says. "I'd come to the States with the notion that mass-produced television was the wave of the future, but Westinghouse thought that commercially, television just wasn't very important. So I left." But within a year Zworykin returned and got the go-ahead to work on his television project. By 1923 he had developed the iconoscope and kinescope and welded them into a working electronic TV system, putting it through its paces before a group of Westinghouse executives.

"By present standards the demonstration was scarcely impressive," he says. "The transmitted pattern was a cross projected on the target of the camera tube; a similar cross appeared, with low contrasts and rather poor definition, on the screen of the cathode-ray tube." Still, Zworykin had proven TV could work. And was Westinghouse impressed? "Hardly at all," he recalls. "The president seemed amused, but asked me to please do something more useful. With that single utterance he dismissed my biggest dream. I almost fainted."

Still Zworykin made a hit with his television system at the Institute of Radio Engineers in Rochester, N.Y. in 1929, and that same year a fateful encounter occurred. He met David Sarnoff, then vice president and general manager of the Radio Corporation of America, which had been founded only ten years before. "Sarnoff quickly grasped the potential of my proposals," says Zworykin, "and gave me every encouragement from then on to realize my ideas. Without him there's no telling how long the advent of TV would have been delayed." Sarnoff hired Zworykin to head RCA's Electronic Research Laboratory in Camden and by 1931 the scientist and his staff had made dramatic improvements on both the kinescope and iconoscope.

While marketing plans for television were being worked out, Zworykin was involved in other scientific endeavors and by 1934 had taken to traveling abroad extensively for RCA. One trip to Lebanon brought him perilously close to death. "This was just after the start of World War II," he says. "I flew from Beirut to London, where I planned to board the S.S. Athenia en route to New York. But I had inadvertently left my tuxedo behind in Lebanon, and rather than endure the embarrassment of being improperly dressed in the first-class dining room during the crossing, I decided to shop for dinner dress and take a later ship." The Athenia, minus Zworykin, was torpedoed by a German U-boat off the coast of Ireland. Among the dead were 28 Americans.

In the war's closing years, Zworykin's work at RCA was principally in support of the Allied effort. He created an infrared imaging tube capable of converting invisible infrared rays into visible light, and this became the basis of the "sniperscope" and "snooperscope," used by Allied troops to spy on enemy encampments in the dark without being seen themselves. "We would test the tube by driving around Princeton late at night with our headlights off," Zworykin says. "Once we were stopped by police who thought we must have been spies riding around in a car without lights near the RCA Labs."

After the war, Zworykin's attention was drawn to developing new uses of electronics. He worked with Dr. John Von Neumann, of the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton, on projects for electronic weather forecasting and hurricane control. Other projects included computer-operated stoplights to prevent traffic congestion, and highway radio transmitters that would automatically control specially-equipped vehicles, thus eliminating road accidents. There was also the electron microscope, developed in the early 1940s with Zworykin's guidance by a group under James Hillier, who was later to become RCA's top-ranking scientist. Now used by medical researchers, microbiologists, metallurgists and electronics engineers throughout the world, the device focuses beams of electrons, rather than lens-refracted light, to project a greatly magnified image on a fluorescent screen. Zworykin considers it yet another manifestation of his interest in using electronics to "see what you normally cannot see."

Zworykin has been called "the father of television," but he wears the title uneasily. "It's really not the case at all," he insists. "A lot of people contributed to the development of television. I've always viewed modern scientific progress as a ladder, with my own contribution just one of many rungs." While much has been made of Zworykin's pronounced disenchantment with most television fare, he and his wife, Katharine, a retired pediatrician, do own an RCA color set which gets more than infrequent use in their Princeton home. "Naturally I spend a lot of time at home reading in my den, keeping au courant on new developments in the sciences," he says. "But if my wife is watching television and a program comes on that she knows I'll enjoy - a symphony concert, a good lecture, something about wildlife or underseas exploration - she will call me in." When he can spare time from his work, Zworykin likes to hunt pheasant, accompanied by his retriever, Lucky.

Which is not to imply that Zworykin is a man of leisure. At the scientist's retirement dinner in 1954, then RCA Chairman David Sarnoff recounted an occasion when Zworykin was driving to work with some colleagues during an early morning snowstorm: "They became snowbound, the automobile was stuck and could not move. Dr. Zworykin closed his eyes, reclined and said, 'Now it is time to go to work.' That is the way he went to work - by closing his eyes and dreaming and thinking and planning. And doing."

- Nov/Dec 1978 RCA Communicate

Television pioneer, Dr. Vladimir Kosma Zworykin died at the Princeton Medical Center on July 29, 1982, one day short of his ninety-third birthday. Elected an Honorary Vice-President of the RCA Corporation upon his retirement in 1954, Dr. Zworykin was often called the "father of television." However, he declined the accolade, telling interviewers that hundreds contributed to television over many years. He preferred to compare television's development with the building of a ladder, explaining that as each engineer added a rung, "It enabled the others to climb a little higher and see the next problem a little better."

"Father" or not, there is no question that the achievement of practical television stems to a large extent from Dr. Zworykin's pioneering work in the 1920s and 1930s. His conception of the first practical TV camera tube, the iconoscope, and his development of the kinescope picture tube formed the basis for almost all important later advances in the field.

A Russian immigrant, he came to the United States after World War I and worked for Westinghouse in Pittsburgh from 1920 to 1929. It was there that he did some of his early work on television. But it was not until he teamed up in 1929 with another Russian immigrant, Gen. David Sarnoff, later President and Chairman of RCA, that his television work got the management and financial backing that enabled Dr. Zworykin and the RCA scientists working with him to develop television into a practical system. Both men never forgot their first meeting. In response to Gen. Sarnoff's question, Dr. Zworykin, thinking solely in research terms, estimated that the development of television would cost $100,000. Years later, Gen. Sarnoff delighted in teasing Dr. Zworykin by telling audiences what a "great salesman" the inventor was. "I asked him how much it would it cost to develop TV. He told me $100,000, but RCA spent $50 million before we ever got a penny back from TV."

Dr. Zworykin was born on July 30, 1889, in Mourom, Russia, where his father owned and operated a fleet of boats on the Oka River. As the owner's son, he had the run of the ships and often played with the pushbuttons used to signal the engine room from the bridge. Thus, Dr. Zworykin would tell interviewers, he was intrigued with electrical communications well before he was lO years old.

Perhaps because of this interest in communications, his father sent him to the Petrograd Institute of Technology which awarded him an Electrical Engineering degree in 1912. At the institute, Dr. Zworykin studied under, and assisted, Professor Boris Rosing, to whom Dr. Zworykin credited both his decision to become a scientist and his special interest in television and electronics. As early as 1906, Prof. Rosing believed that the solution to practical television was to be found, not in mechanical systems, but in the employment of cathode ray tubes. Dr. Zworykin's iconoscope and kinescope followed this line of reasoning.

In 1912, Dr. Zworykin entered the College de France in Paris, where he studied X-rays under the noted scientist Professor Paul Langevin. His studies were interrupted by World War I and Dr. Zworykin had to return to Russia to serve in the Army Signal Corps. After the war, he came to the United States, becoming a citizen in 1924. He received a doctorate from the University of Pittsburgh in 1926.

Soon after arriving in the U.S., Dr. Zworykin joined the Westinghouse research staff and began investigations in the field of photoelectric emission. He also resumed his research in television. Dr. Zworykin became associated with RCA in 1929. He served as Director of the Electronic Research Laboratory. first in Camden. N.J and from 1942 until his retirement in 1954, at Princeton, N.J.

In addition to TV. Dr. Zworykin applied his talents to a broad field of electronics and held more than 120 U.S. patents on developments ranging from gunnery controls to electronically controlled missiles and automobiles. Because of Dr. Zworykin's research activities, important devices such as various forms of secondary emission multipliers and image tubes were developed and perfected. The "Snooperscope" and "Sniperscope" - important military developments in World War II - were practical applications of research on infrared image tubes.

Dr. Zworykin's intensive study of electron optics directed his interest to the electron microscope. RCA's pioneering in the commercial development of the electron microscope typifies Dr. Zworykin's genius - not only his scientific expertise but his ability to attract and motivate good scientists. In 1940, he hired a young Canadian graduate student. Dr. James Hillier, to work on the electron microscope. Dr. Hillier. who retired in 1977 as Executive Vice-President and Chief Scientist of RCA. decided to work for RCA because Dr. Zworykin recruited him with one question - how long would it take Dr. Hillier to build an electron microscope, while other prospective employers engaged Dr. Hillier in theoretical discussions or emphasized their good working conditions and fringe benefits.

Working under Dr. Zworykin's guidance, it took Dr. Hillier little more than three months to build the first RCA electron microscope. Coincidentally, just three years after Dr. Zworykin was elected to the U.S. National Inventors Hall of Fame for his development of television, Dr. Hillier was elected in 1980 for his work on the electron microscope.

For a period of years following his 1954 retirement, Dr. Zworykin directed a Medical Electronics Center at the Rockefeller Institute in New York. In this capacity, as National Chairman of the Professional Group on Medical Electronics of the Institute of Radio Engineers, as Founder-President of the International Federation for Medical Electronics and Biological Engineering, and as Member of the Board of Governors of the International Institute for Medical Electronics and Biological Engineering Paris, he worked for the development of the use of electronic methods in medicine and the life sciences.

Dr. Zworykin was often asked if, while working on television, he ever envisioned the worldwide entertainment media it became. He would reply that he hadn't, and credited Gen. Sarnoff with seeing TV as a new form of home entertainment. Dr. Zworykin would then go on to explain that in his early years he looked upon television as a system that would enable man to see things in places where his eyes couldn't reach. Thus, he was delighted with the first television pictures of the back side of the moon. And, when he visited the Jet Propulsion Laboratories in California to see the reception of pictures of Mars, he remarked, "This is what television is really for."

Dr. Zworykin curtailed his activities, spending winters in Florida, but never gave up his interest in scientific research. For many years. he was a Visiting Professor for the Center for Theoretical Studies and the Institute for Molecular and Cellular Evolution of the University of Miami in Florida. And he maintained an office at RCA Laboratories. Even at the age of 91, he would drive from his home in Princeton to his office in the David Sarnoff Research Center to read his large collection of scientific journals and reports.

In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson awarded him the United States' highest scientific honor, the National Medal of Science "for major contributions to the instruments of science, engineering, and television, and for his stimulation of the application of engineering to medicine." Including the Medal of Science. Dr. Zworykin received virtually every major scientific honor among 27 major awards and numerous others from groups throughout the world. He was elected to such prestigious American societies as the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the National Academy of Engineering.

- Sep/Oct 1982 RCA Engineer

Dr. Zworykin, or "The Doctor," which is the name by which many of us knew him, was unquestionably a great man; but I often wonder if any one of us, as an individual, is capable of appreciating the full measure of his genius. Like so many of the great people of history, The Doctor had breadth - breadth of interests, breadth of knowledge, of capabilities. He was a great inventor, but he was also an entrepreneur, a humanist, a practical psychologist, and a philosopher.

As you know, I was very close to The Doctor, both professionally and personally. I was always impressed by the visions that he constantly projected. After a while, I began to realize that his visions had a consistent theme - to use technology to enable people to do something that they wanted to do, but that they could not presently do.

His visions were not the idle daydreams of a gadgeteer. Yes, technical invention was usually the cornerstone of each of his visions, but the larger part of each vision was the outline of a complete plan for making it happen. When he explained his visions, technical people tended to hear only the technical parts. I was among those in the beginning. Business people heard only the business parts and so on. But with The Doctor, the vision was total. He dedicated his life to realizing those visions. For that, we ordinary mortals will forever be in his debt.

I would like to pass on a few personal thoughts regarding the breadth of The Doctor's personality. While The Doctor is notorious for his grossly inadequate estimate of the cost of developing television, his notoriety tends to mask the fact that he did sell he concept to General Sarnoff, and moreover, kept it sold in spite of delays and overruns.

In the laboratory, he had a very special ability to select or develop first-rate research workers. I was never sure whether he was good at selecting, or at developing, or both. It does not really matter. The fact is that there is a substantial roster of people from The Doctor's activities who have developed international reputations. Several of them are here today. There are several of us who remember The Doctor's daily visits to our laboratories, his suggestions, his needling, his discussions, his proddings. While at times he made us uncomfortable, and at times we even rebelled, the fact is, we ended up being better engineers and scientists and, on occasion, surprised even ourselves with our accomplishments. One part of his genius was his ability to inspire people to do better than their best.

He was completely impatient with bureaucracies in any form, and I used to believe he derived some kind of pleasure from finding ways to by-pass them. It was once my private story that he hired me on speculation and that it was not until I had been working for him for several months that I learned that I had no budget whatsoever. The Doctor had assumed, correctly, that it would take the accountants that long to catch up with him. I learned from that experience that his real passion was to remove any obstacle that stood in the way of "getting the job done."

In case you think that I am painting the picture of a superman, let me remind you that The Doctor was also very human. He was a good husband, as Katusha will attest, a good father and a good friend. His breadth also showed through in the wide range of his personal interests when away from his job. He had a plethora of friends from all walks of life that paralleled those interests: philosophers, writers, musicians, artists, politicians. Many, of course, were from the Russian community. Then, there were hunting companions, tennis opponents, and more. At one point in his life he even took a short excursion into flying his own plane. To be his friend was always an exhilarating experience.

Being human, he also had some foibles. As one example, he never quite believed that he had a heavy Russian accent. Yet on more than one occasion, when we had visitors at the Labs, I found myself translating for The Doctor even though he was speaking perfectly good English. I hope that these brief glimpses of The Doctor through one man's eyes have at least conveyed the message that I, for one, held him in the highest regard, not just as an illustrious inventor, but as a great man.

Dr. Zworykin has passed on. But I like to believe he died a happy man, having lived long enough to see the realization of his early great vision - to have technology take our eyes where our bodies cannot follow. While I cannot say whether he envisioned all the ramifications of the technology he initiated, I can say that the whole world is richer for his having lived.

- 1982 Tribute by James Hillier

Read Vladimir Zworykin's Oral History at the IEEE History Center.

Search for patents issued to Vladimir Zworykin.

If you have some additional information to supply on Vladimir Zworykin, feel free to submit the form below, so your comments can be added to this page.

Send your comments in email via the Contact page